The Road to Rancho Escondido. Baja California, Mexico

Incredible drive, an unexpected stay,and the remarkable hospitality of the Mexican People.

I turned my overladen Jeep onto a sandy road that slowly became more sand and less road. It isn’t really sand, I suppose. The soft talc-like Baja dust floats in the air. Infiltrates every crevice of the Jeep through the big gaps in the soft top. Not to mention your nose, eyes, ears, mouth. Everywhere.

I have a neck scarf as a mask, but Scout has nothing. Poor doggo.

I had heard that there was a relatively unmarked/untrampled set of cave paintings in the rugged hills and was off in search of it.

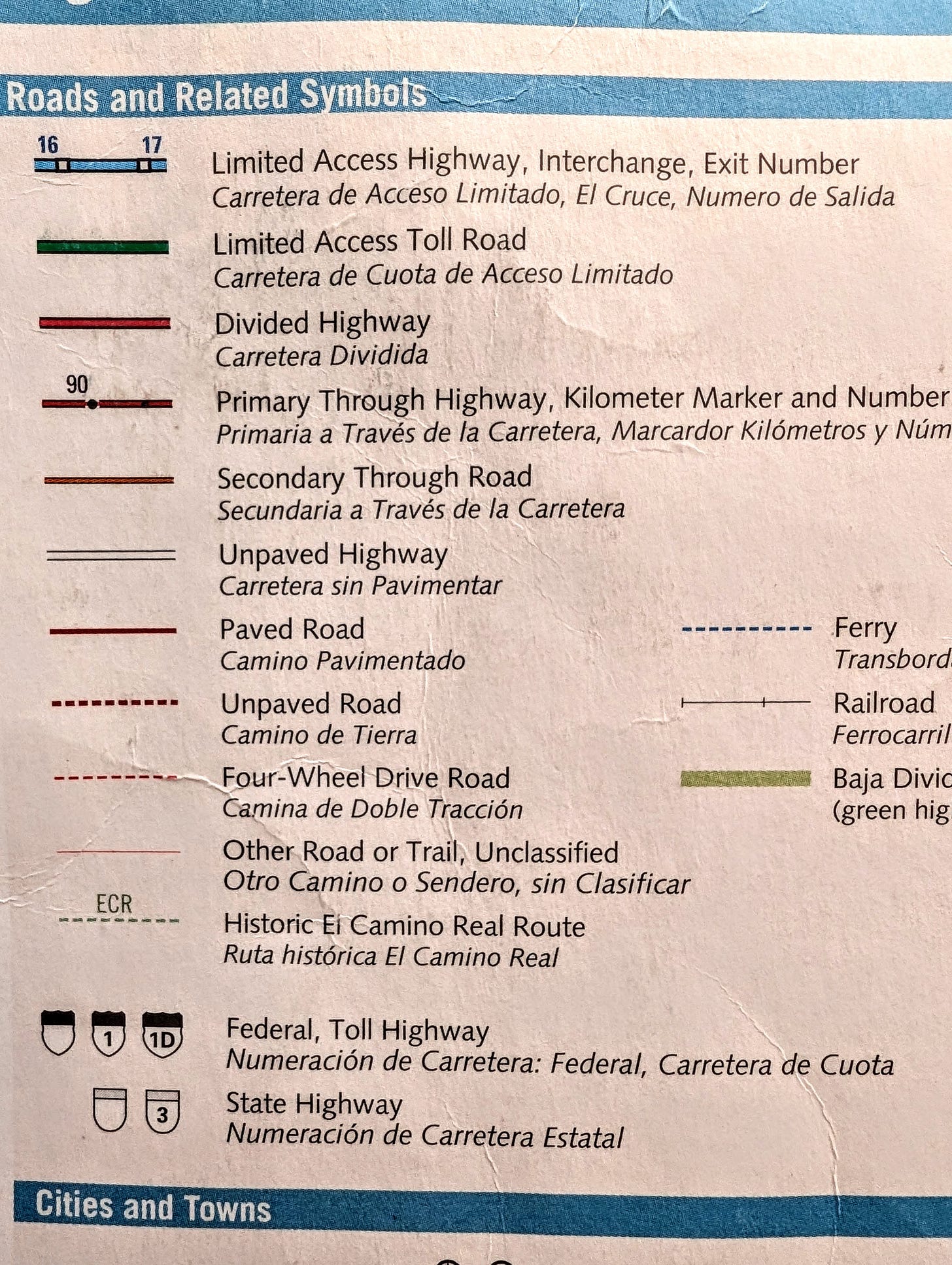

Baja Atlas

The indispensable Baja Atlas is the reigning travel champion throughout this special Mexican peninsula. It includes a pretty good assessment of the travelability of the various types of roads. Parts of this trip were certainly ‘otro camino.”

The incredible Baja Divide Trail ran along much of this trip. It can be hiked or biked. Along this way I met a couple from Poland who were tackling the fill Divide trip on bikes. I left water along the trail the next day to lighten their loads.

Valle de Los Cirios

Valley of the Candles.

This is a bio-reserve covering almost 10000 square miles, stretching from the Pacific to the Gulf of California. It is the second largest on the peninsula and is home to a remarkable biodiverse collection of flora and fauna.

1 Valle de los Cirios, Wikipedia

Cardon Cactus

What many confuse for the saguaro cactus (seen in the Sonoran desert in Arizona and the Mexican State Sonora) these are actually a cardon cactus. (and the “Cirios” are Boojum Trees! )

These giants form branch trunks closer to the base vs the arms of a saguaro. Both are ancient and keystone species which makes their destruction for, say, the construction of large walls a shameful act.

2 San Diego Natural History Museum Field Guide: Cardon Cactus

Baja Travel Rules and the Ticking Clock

There are a couple of good rules for driving in Baja, one of which I abide by like it is religion.

Rule #1: No driving after dark.

The reasons are far less nefarious than most Americans presume. In the desert, after dark, you can’t see cattle when they are laying in the road.

Nobody needs to hit a cow in the dark.

For what it is worth- The best part of making this a rule is that you are always done in time to enjoy where you are. To actually be present.

By now, I had traveled only 70 miles in 6 hours.

(Though in all fairness- lots of non-moving time for photos!)

My navigation plan had completely failed me. It was late afternoon and I was still hours from finding the cave paintings, and the light was starting to turn.

I had read of a ranch on this road might be able to accommodate travelers, so I pressed ahead.

Show Me A Sign

At a sandy crossroads one sign pointed to the “nearby” waterfront camp “San Fransisquito” that I had heard had been long abandoned, so I turned away towards the ranch marked on the Atlas.

After some time, signs of life started to appear. Barbed wire fencing marking land edges, and in the distance. A building.

At the Gates of Rancho Escondido

I stopped outside the gates of the Rancho as a pack of dogs met me on the other side with a racket. After some time a woman made her way down the long drive from the house to the gate and I explained that I wanted to get off the road for the night and asked if I could camp nearby. She invited me in and swung the gates wide for me.

I parked the Jeep where she indicated and prepared to set up camp when she invited me to stay in one of the rustic cabins under the great dining palapa. Inside was a simple bed and night table. I set up a bed for Scout on the floor.

With a knock on the door, my new friend came in to hang a round mirror on the wall and some fresh towels so I could clean up for supper.

After 3000 miles across the US and a few days camping on beaches in Baja- having a bed, a roof, great coffee and outstanding hospitality, I stayed on for another full day. Scout became one of the dog pack, roaming free around the Rancho and learning where the back kitchen door snacks can be found.

On “Adios”

One thing about spending time with these special people and places is that I find it hard to acknowledge that there is a high likelihood of never returning. Rancho Escondido is a special place but it was along a path I was traveling that I don’t imagine traveling again. It makes it hard to say good bye. But eventually we set back out to get to the caves.

If you are ever Bahia de los Angeles and have a qualified vehicle, make the trip to Rancho Escondio. They have a number of cabins now and welcome visitors. The hospitality is very special there.

Mesa el Carmen

We turned back to the road and left a dust cloud behind us as we headed on towards the site of the cave. (Questioning my fuel supply, I stopped at another ranch and bought some fuel from the farmer there.)

The trail to the cave is unflagged, but clear. It is steep and covered in all manner of cacti that like to come along for the ride.

At the cave, the memories of a previous civilization are emblazoned across all surfaces. Carbon dating has recently changed the idea on the age of these paintings, suggesting that they may be as old as 8000 years.

This is a remarkable, unrestricted access to an archeological treasure that allows a close view at the art. If you visit, use extreme caution, don’t touch anything, take only photos, watch your footing, leave the walking sticks, etc.

There are many ideas about what the paintings depict- a great hunt, a race of giants, migrations- truth is lost to history. Though I must say that while at Carnival in La Paz a few weeks later- it could be as simple as a recording of a great party. The Substack/Gram of 10,000 years ago.

Thoughts on Hospitality and Privilege

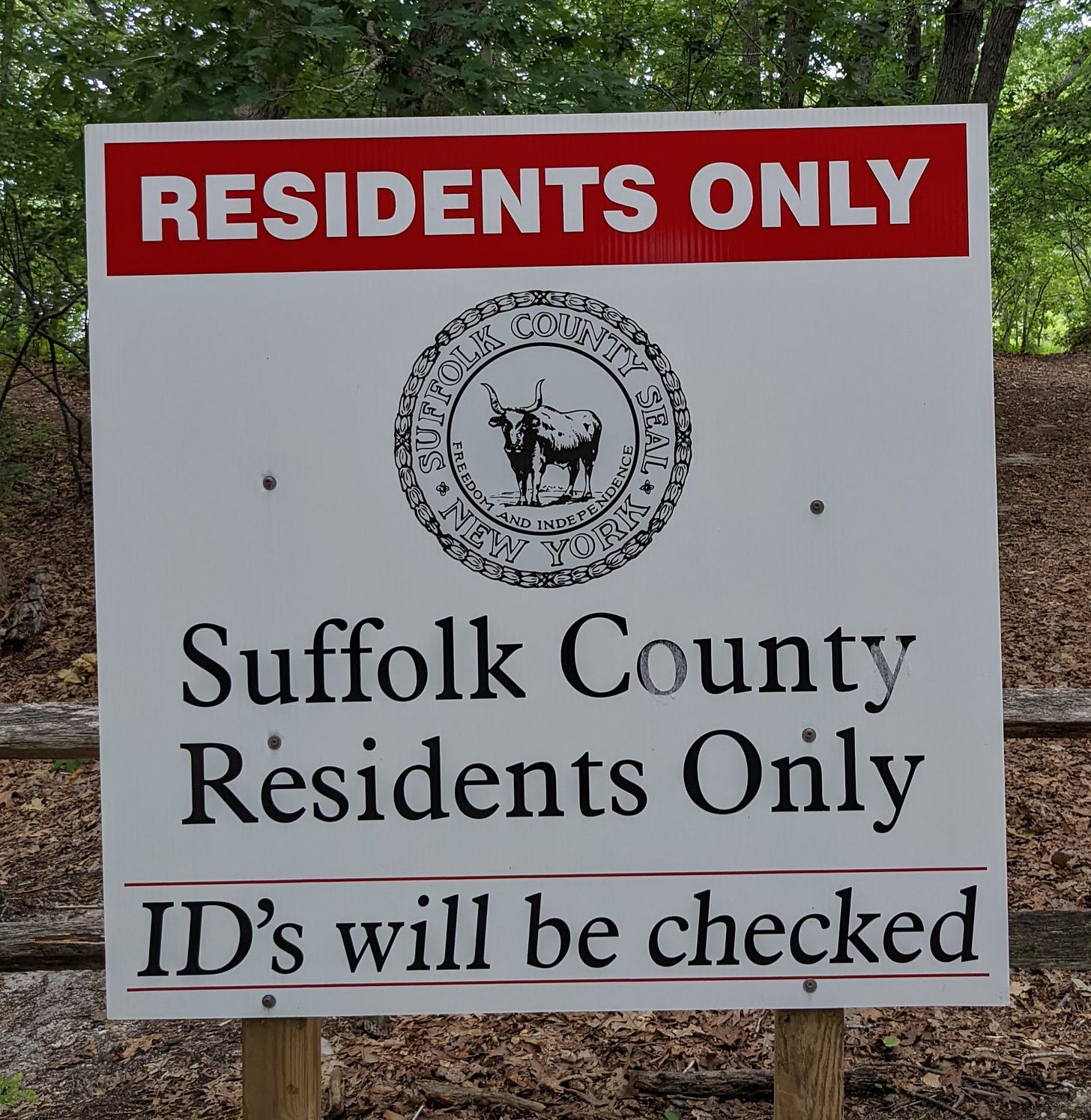

Along the way, and repeatedly over 6 weeks of unfettered travel throughout Baja California and Baja California Sur- camping upon beaches and in small villages. In cities and everything in between. Along the way I had the nagging personal acknowledgement that if a Mexican in a very questionable car such as mine were to roll up at my driveway asking for a room, I would not likely have answered as well. And I will strive to fix that. Then, more broadly, as we see public access to nature in our home area become more and more restricted, to keep out all strangers, I know that we become weaker for it.

I will forever be grateful to the people, culture and places of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula for being the better people.

Home:

In 10,000 years, what will people know about what we did here.

Valle de los Cirios ("Valley of the Candles") is a wildlife protection area in the southern portion of the municipality of Ensenada in Baja California, Mexico. At 2,521,776 hectares (9,736.63 sq mi) in area, it is the second-largest wildlife protection area behind El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, but it includes more land than El Vizcaíno.

Geography

[edit]

Valle de los Cirios is located in central Baja California. It covers a third of the area of the state of Baja California and half the territory of Ensenada municipality. Its southern border is the state line with Baja California Sur, where it adjoins El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve.[1] The two protected areas together cover more area than the state of Quintana Roo. Valle de los Cirios borders the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of California

Pachycereus pringlei

Elephant Cactus, Cardón, Cardón Pelón

CACTACEAE (Cactus Family)

The generic name refers to the lower portion of the trunk that resembles an elephant's leg: pachy, "stout trunked," and cereus, "columnar cactus." The specific epithet refers to Cyrus Guernsey Pringle who was a Quaker, American botanist, and plant collector. He also was a plant breeder on his farm in Vermont, keeper of the herbarium at the University of Vermont during 1902, and collected extensively in the Pacific states and Mexico between 1880 and 1909.

Description

A giant cactus growing to 20 m (60 feet) high with a columnar trunk up to 1.5 m (4-1/2 ft) wide. The trunk and branches have 11 to 17 ribs covered with many areoles of 20 to 30 gray spines. White flowers bloom from March to June, and then form tan bristly fruits.

(The photograph at right is the trunkless form typical to islands in the Gulf of California. See next page for a photograph of a very tall specimen — with a trunk — taken on the peninsula near Cataviña.)https://www.sdnhm.org/oceanoasis/fieldguide/pach-pri.html